Scientists discover a potential Zosempic rival who could help people lose less nausea

Vegovi, eat your heart. In a new research document, scientists say that they have found a naturally occurring hormone that can help people lose weight while avoiding side effects often associated with semi -giggles (the active ingredient in Ozepik and Vegovi) and similar drugs.

A team of Stanford Medicine researchers conducted the study, published Last week at Nature magazine. With the help of artificial intelligence, the team identifies the unknown peptide that looks safely reducing the appetite and weight of mice and miniature pigs, without causing nausea or other gastrointestinal symptoms. More studies will be needed to check the safety and efficiency of the molecule in humans, but the findings provide a striking examination in what could be the future of treating obesity.

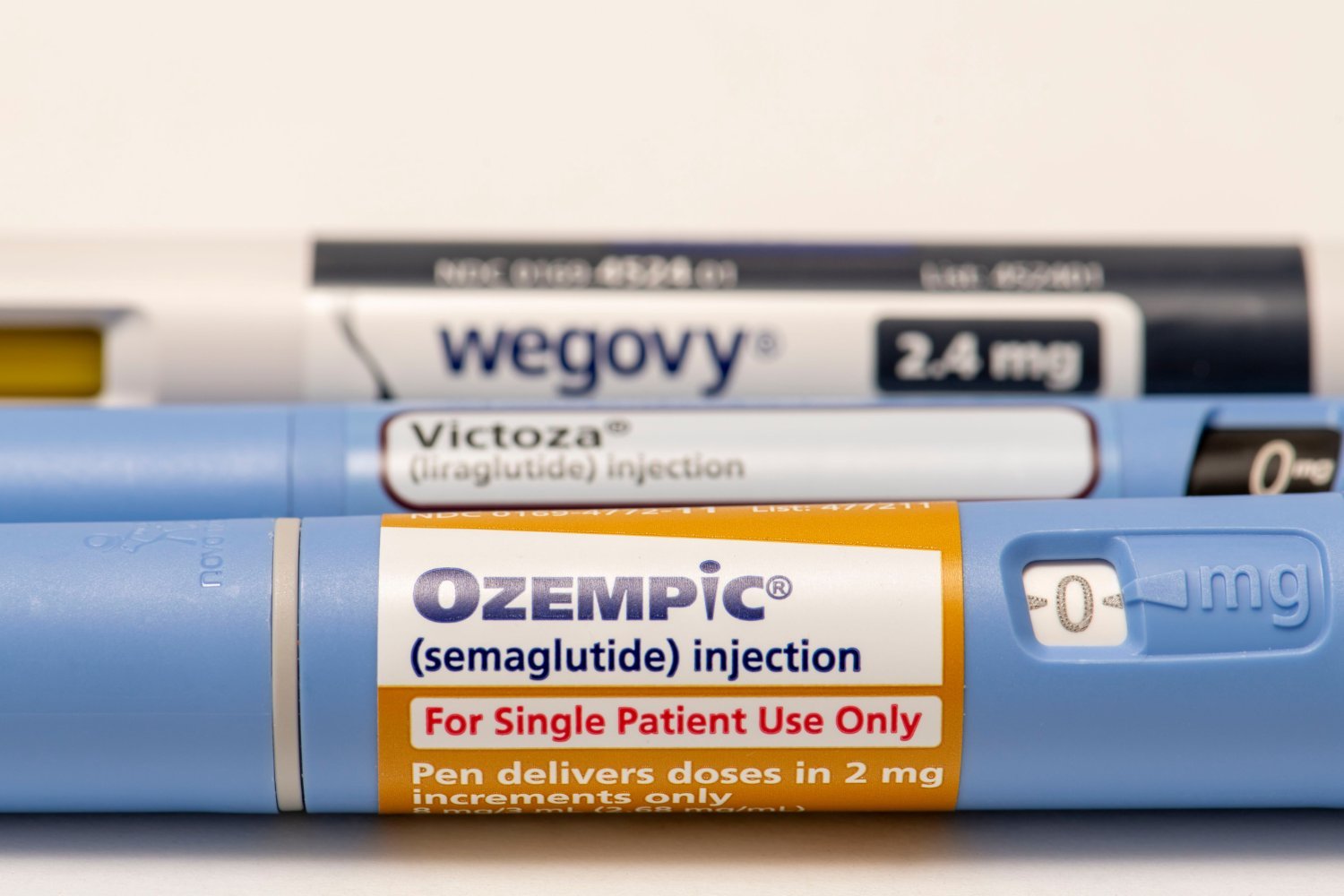

The appearance of a semi -giglide and similar drugs in recent years has been Truly revolutionary For the field of medicine for obesity. These medicines, also used for type 2 diabetes, proved to be far more effective in helping people lose weight from diet and exercise, with results varying from 15% to 20% Weakened in clinical trials. Semaglutide works by imitating GLP-1, a hormone that helps regulate our appetite and metabolism, among other functions (some drugs such as thyrcepatide imitate both GLP-1 and other related hormones).

As innovative as these drugs may be, they are known that they often cause annoying symptoms of GI and can rarely cause more severe complications such as gastroparesis (gastric paralysis). Scientists are also working to find and develop more -generation drugs that could provide even more weight loss or offer other amenities, such as being available as a pill. In this sense, Stanford’s medical researchers have set up a new strategy to find their drug candidate.

Many hormones in the body are activated only when their precursors are split from specific enzymes. These precursors are called prohormones, and the family of enzymes that cut them are called prohormone converted. Researchers have examined one of these enzymes, Prohormon Convertase 1/3, which is known to help produce GLP-1. They decided to see if they could find other useful hunger hormones naturally produced by the enzyme. To significantly accelerate this detection process, they have developed a computer algorithm (a direct peptide predictor) to narrow the list of potential molecules that meet their criteria.

This screening has discovered an initial batch of 373 prohormones that can give about 2,700 different peptides (peptides are often the building blocks of larger proteins, but they can have their distinctive functions in the body). From there, the researchers tested 100 peptides who know or suspect, can affect the hungry brain drive (including GLP-1 for comparison). And in the end, they identified a molecule that looked particularly promising, a 12-amino acid peptide called a peptide associated with Brinp2, or Brp.

Scientists then tested BRP on laboratory mice and miniature pigs (it is believed that minipigs resemble people metabolically). They found that one dose of BRP significantly reduced the appetite of both animals in the short term, sometimes by as much as 50%. And the obese mice given BRP significantly weaken for a two-week period, with most of this weight stored fat.

Further experiments showed that the effects that reduce the hunger of BRP on the brain did not include GLP-1 receptor at all, and this simply did not cause animals to experience the symptoms of GI, which are usually associated with ozepik-like drugs. Dosage animals also did not have changes in their movement, the level of anxious behavior, or water intake, suggesting that BRP may be safely tolerated when taken as a medicine.

“The receptors directed by semaglutide are found in the brain, but also in the intestines, pancreas and other tissues. Therefore, Ozepic has widespread effects, including slowing food movement through the digestive tract and lowering blood sugar levels. “Senior research researcher Catherine Svenson, Assistant Professor of Pathology in Stanford, in A statement from the university. “In contrast, Brp appears to act specifically in the hypothalamus that controls appetite and metabolism.”

The findings of the team, of course, are preliminary at this point. It will take a lot more time and research, including early successful clinical trials in humans, before BRP is considered as the next big thing in treating obesity. But the discovery of the team is the most native that suggests that the semaglutide has indeed caused a maritime change in the treatment of obesity. There are now dozens of experimental drugs in the pipeline that threaten to rival or even surpass Ozepic/Wegovy, including various formulations of semaglutide. Svenson and her colleagues, for their part, have already submitted patents to BRP and she is the co -founder of a company that hopes to develop the clinical use molecule.

No medicine comes without side effects, but the future of treating obesity can someday involve much less nausea.