Saltwater may pollute 75% of coastal freshwater by 2100

Rising sea levels are causing visible damage to coastal communities, but we also need to worry about what’s happening below our line of sight, disturbing new research suggests.

New research from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the US Department of Defense (DOD) suggests that this seawater will contaminate groundwater in approximately 75 percent of the world’s coastal areas by the end of the century. Their findings, published at the end of last month Geophysical Research Lettershighlight how rising sea levels and decreasing rainfall contribute to saltwater intrusion.

Underground fresh water and ocean salt water maintain a unique balance beneath the coasts. The balance is maintained by the internal pressure of the ocean, as well as precipitation, which replenishes freshwater aquifers (underground layers of the earth that store water). Although there is some overlap between freshwater and saltwater in what is known as the transition zone, the balance generally keeps each body of water on its side.

However, climate change favors salt water in the form of two environmental changes: rising sea levels and decreasing precipitation due to global warming. Less rain means that aquifers are not fully recharged, weakening their ability to resist the intrusion of saltwater, called saltwater intrusion, that comes with rising sea levels.

Saltwater intrusion is exactly what it sounds like: when saltwater moves inland more than expected, often threatening freshwater supplies such as aquifers.

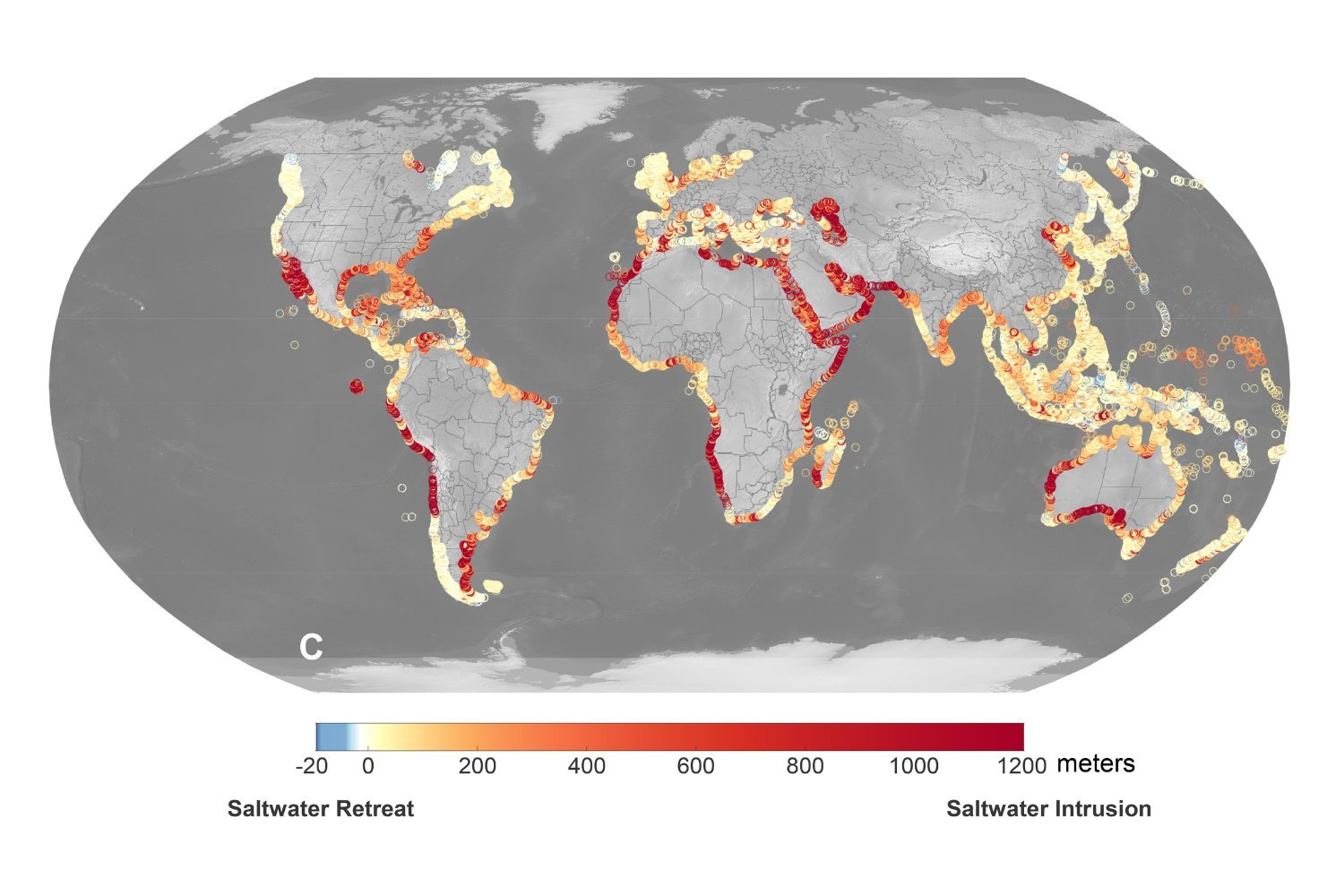

To study the future extent of saltwater intrusion, JPL and DOD researchers analyzed how rising sea levels and declining groundwater recharge will affect more than 60,000 coastal watersheds (areas that drain water from features such as rivers and streams into a common water basin) worldwide by 2100. .

As detailed in the study, the researchers concluded that by the end of the century, 77% of the coastal watersheds studied will be affected by saltwater intrusion due to the two aforementioned environmental factors. This is over three out of every four coastal regions assessed.

The researchers also looked at each factor separately. For example, rising sea levels alone will move saltwater inland in 82 percent of the coastal watersheds considered in the study, specifically pushing the freshwater-saltwater transition zone back as much as 656 feet (200 meters) by 2100. Low-lying regions such as Southeast Asia, the Gulf Coast, and parts of the US East Coast are particularly at risk.

On the other hand, slower groundwater recharge would allow saltwater intrusion in only 45% of the watersheds studied, but would push the transition zone inland by three-quarters of a mile (about 1,200 meters). Areas including the Arabian Peninsula, Western Australia and Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula will be vulnerable to this event. However, the researchers also note that groundwater recharge will actually increase in 42 percent of the remaining coastal watersheds, in some cases even outpacing saltwater intrusion.

“Depending on where you are and who dominates, your management implications may change,” said Kira Adams of JPL and co-author of the study at JPL statementciting rising sea levels and depleted aquifers.

Sea-level rise is likely to influence the impact of saltwater intrusion on a global scale, while groundwater recharge will indicate the depth of local saltwater intrusion. However, the two factors are closely related.

“With the intrusion of salt water, we see that sea-level rise raises the underlying risk for changes in groundwater recharge to become a serious factor,” said JPL’s Ben Hamlington, who also led the study.

Global climate approaches that account for local climate impacts, such as this study, are essential for countries that lack the resources to conduct such research independently, the team stressed, and “those with the fewest resources are the most affected by sea level rise and climate change,” Hamlington added.

The end of the century may seem like a long way off, but if nations and industries are to mobilize in response to these predictions, the year 2100. it will happen sooner than we think.