Brooke Shields feels “more confident” than ever as she turns 60

Brooke Shields spent much of her life trying to be nice. As a teenager, she smiled politely when reporters asked if she felt over-sexualized and exploited in films like the 1978 film. Beauty and her instantly iconic Calvin Klein ad two years later. She was an obedient daughter to her mother and ruler, Terrywhose alcoholism made their close bond indescribably difficult. She smiled for the cameras as they followed her to Princeton University in 1985 and asked (as if it was their business) that she was a virgin. Young Brooke Shields was a master of standing out and being cute.

As she grew up, she continued to shine, but used her voice more defiantly – most memorably in 2005 New York Times published response to Tom Cruise‘s an attack on her use of antidepressants during postpartum depression after the birth of her first daughter, Rowan. She showed off her comedic chops in four seasons of her NBC sitcom, Suddenly Susanand several Broadway shows. She published two New York Times bestselling memoirs.

Then she had the courage to do something (apparently) unexpected: she began to grow old. Although her confidence and joy have grown with age—she turns 60 this spring—she writes in her new book, Brooke Shields is not allowed to age: Thoughts on aging as a woman (on sale Tuesday, January 14), “I began to notice that my external perception didn’t seem to match my internal well-being. My industry no longer welcomed me with the enthusiasm I expected. Casting agents and producers, as well as my fans, were watching more: to stop time… and maybe even turn it back.”

To borrow a phrase from her book, yuck. Frustrated by being “overlooked at the exact moment I felt I was in my prime,” she writes, she added a new entry to her resume in 2024: Founder and CEO of Commence, an online community and grooming brand behind the hair, intended for women over 40 years old.

“The more I’m expected to be invisible, undemanding, or disappear so I can be frozen in time as a certain (read: younger) version of Brooke Shields,” she writes, “the more fully I intend to stand high and take place as the woman I am now.’ The star once known as America’s sweetheart talks to us about its accession to power.

The book opens with you and your daughters, Rowan, now 21, and Grier, 18, walking down the street and realizing that people are looking at them and not at you. Tell me us about it.

The conflicts we feel—they hit you right away. There’s this protection, this pride and joy, and then there’s this reflection of who you’re not anymore, technically. And I am not saying that there is envy or jealousy, but it is a restructuring: they start their journey when you reach a level that is hopefully (more) happy and calm, but accompanied by a lot of saturated feelings.

It’s the perfect setup for what you write later in the book: “When men stop noticing you, that’s a pretty good indicator of how the world at large will treat you.”

For me, I think anyone who has a daughter in particular can identify with, Oh, my God, I’m not like that anymore. What is my value now?

You talk about learning how to use invisibility to your advantage—allowing people to underestimate you and then exploiting it.

If you don’t get mad at it and find a way to use it, it’s a tool. It’s funny, my girls are all righteous about these things, “How could you say that, Mom?” I’ll say, “My ego has no problem playing this game. I weaken my opponent by making them think I am incapable.’ I found it a source of a certain power and strength.

I used to apologize or start with, “I must be wrong, but…” or “Do you think maybe …?” I don’t need to come weak anymore. And then I don’t have to finish with, “But you better know.”

How did you learn to navigate these conversations?

You can defer and be respectful. I often say, “That’s your area of expertise, and I don’t claim to know a percentage of what you do, but I think…” Then I’m a little more level-headed, and I don’t feel like I have to put myself down to make a point, and before I was afraid to have my opinion.

As a result, many women feel more comfortable and confident in their 40s and 50s. Why is there a belief that middle-aged women are completely miserable?

Because they told us we were miserable. And so if you even look at the nature of the commercials, it’s true, it’s always, “Do you have dry skin? is that you Wump-wop.” That’s what storytelling is, and a cosmetic company, pharmaceutical or otherwise, they’re going to come in and solve all your problems for you. Because if you’re happy, well, what if you don’t need their dry skin cream? So this is all this conspiracy that we were fed.

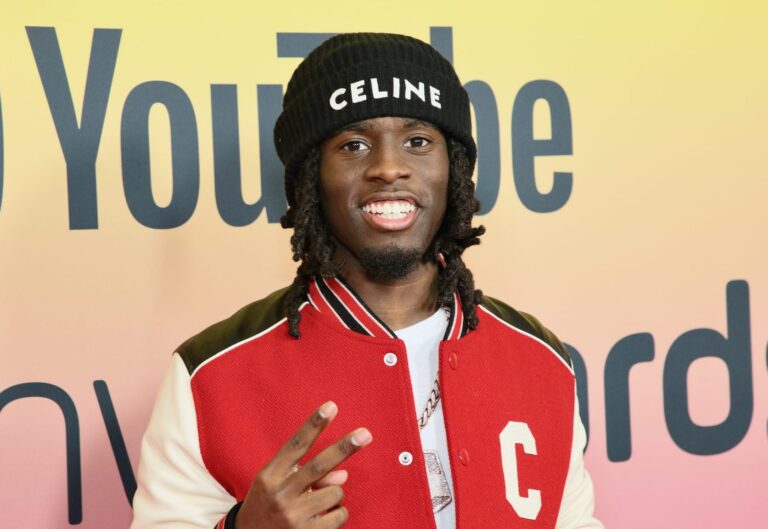

Brooke Shields. Deborah Feingold

This is absolutely correct.

Yes, (aging) does have its downsides, but (we’re) no longer chasing something: you have to have kids by that age, you have to get married, you have to finish college. There are so many decades where we’re just trying to get to the next stage. And then there is a shift.

You’ve noticed that when the pressure is off, older women are more able to be themselves: “We can push the boundaries as we move through the world without everyone watching.”

That doesn’t mean I’m any less ambitious. If anything, I’m probably more ambitious because I feel like I deserve it more. I’m still scared. I’m still nervous, I’m not good enough. I still have to push myself through, (but) we’re getting down to nothing. We’re pretty formidable and I think that scares everyone a little bit.

It takes a different kind of strength to allow yourself the grace to say no – for example, you turned down an invitation to perform with Broadway leading lady Cynthia Eriva and Susan Boyle of Britain has talent. How do you decide when to say no to what seems – at least to everyone else – a great opportunity?

Have a healthy sense of humility, why would you want to do this to yourself? It’s not like I’m “less” as a person, but my capabilities fall short of theirs. I used to think that if I was good enough, I would go and at least hang on, and that would be a feat in itself. But you have to say, “I don’t want that feeling in my stomach that I would definitely feel.”

First you devoted a chapter to being an empty nester, then both of your daughters went to Wake Forest University in North Carolina. “My girls have many skills that I have never used,” you write. Have you worked to get them away from habits you don’t like, such as people-pleasing?

I have one who is a huge people pleaser and I have a younger one who talks about what’s good and what’s bad and doesn’t care what people think. She is very strong in her opinions. Even her reaction—I’ll say, “Aren’t you ashamed?” And she says: “No. No, no.” And she is 18, maybe she will feel differently. My oldest really crosses it, and I don’t know, age, birth (order), whatever—we’re most alike in our approach to life and our actions.

I am so proud to have cleared the space for them to contradict me, express their feelings and not be afraid of being judged. And it’s fine if I don’t agree with them. They just express it to me in different ways.

One thing that stands out about you is how much of your life has been documented. What’s it like to look back and see the girl you once were under so much scrutiny?

I have such empathy. My heart kind of goes out to her and her desperate, desperate need to protect her mom and take care of everything. It felt like this was what I was going to do.

And today?

I see myself now (at Commence HQ) and I never aspired to be in that position. I think about the Zoom I had this morning with one of our investors and how clear it was to me; and how I was in therapy an hour before; and how I lead my children; and how I help my husband get through something; and you just see all these different spokes on the women’s wheel, you know? There is pride because I don’t give a damn if someone doesn’t like me anymore. I mean, yes, you’re in a little pain, but I sit back and think, I don’t even know if I respect you, so why should I be so worried that you like me?